Navtej K Purewal receives funding from the UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

Eleanor Newbigin receives funding from the UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC)

SOAS, University of London apporte un financement en tant que membre adhérent de The Conversation UK.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

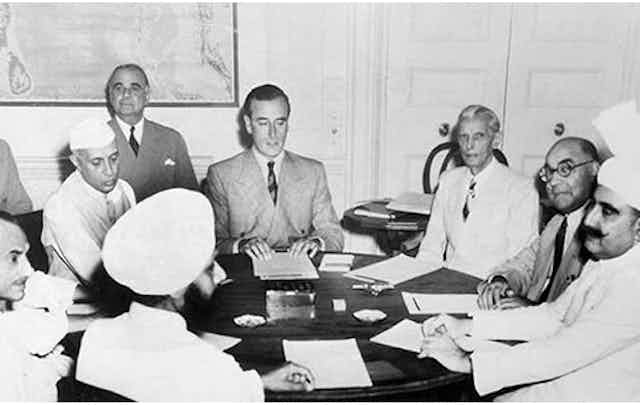

This August marks 75 years since the partition of the Indian subcontinent. British withdrawal from the region prompted the creation of two new states, India and Pakistan.

The process of transferring power grossly simplified diverse societies to make it seem like dividing social groups and drawing new borders was logical and even possible. This decision unleashed one of the biggest human migrations of the 20th century when more than ten million people fled across borders seeking safe refuge.

Anniversaries can be a critical moment to pause and reflect on the passage of time, and reexamine history. Partition is widely seen as the outcome of seemingly irreconcilable differences and inherent religious tension in south Asia. Three-quarters of a century later it’s time to reassess some of the established historical accounts.

Myths have been established around this history based on false assumptions. Here we examine five of them:

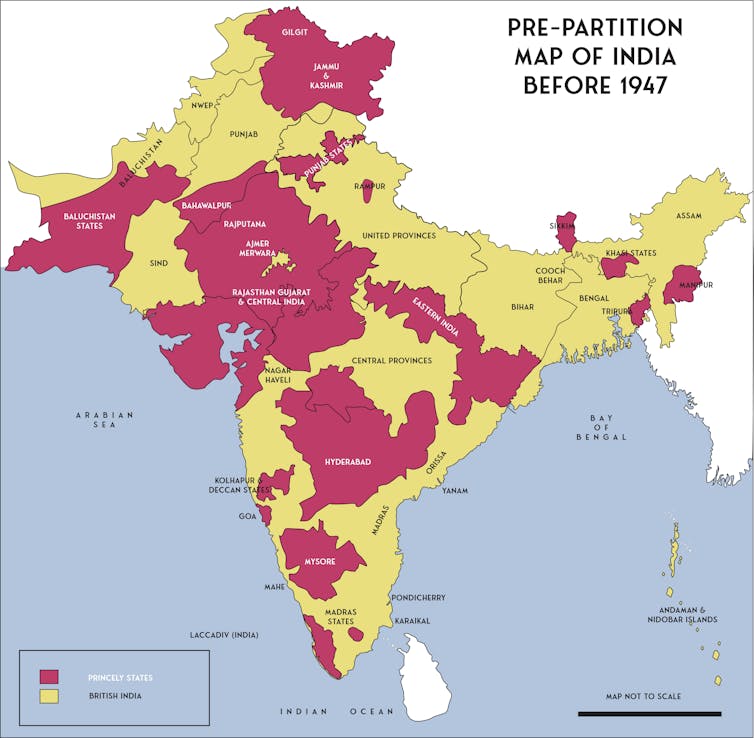

Popular accounts of partition reproduce the British colonial state’s simplistic view of south Asian society just in terms of religious categories – with Hindu and Muslim identities as the biggest groups. Over the decades scholarship has shown that religious difference doesn’t explain partition.

Simplistic religious categories in most analyses of partition fail to sufficiently understand complex social and political issues that shape south Asian societies. Partition pushed people to identify as a particular religion, and even to migrate, based on that identity.

Greater focus on oral histories and personal experiences of partition have highlighted how this action did less to provide a political solution than to impose new divides around national and religious lines.

It ignores huge variation of practices and identities within and across different groups in British India by assuming there was conflict based on religion. Shared cultures based on common language, literature, music and regional and local traditions challenge this.

The tendency to frame partition in binary Hindu vs Muslim terms has helped to shape the rise of religious majoritarianism in post-colonial south Asia, which is based on a constructed, even mythical idea of a majority which makes the rules for everyone, and which can most overtly be seen in the vision of a Hindu nation being advanced by the current government in India.

The western coastal areas of Goa, Daman and Diu were under Portuguese control until 1961 and the south Indian region of Pondicherry/Puducherry was under French colonial rule until 1954.

Estimates of people who migrated across the borders created in 1947 range between 10 million and 17.5 million. Many people from areas directly affected by partition violence, and the insecurities that followed from it, have also migrated beyond south Asia to other parts of the world.

Communities from Punjab, Sindh, Kashmir, and Sylhet form sizeable and significant communities in the UK, Canada, the US, and beyond. This is another reminder of the ongoing repercussions and legacies of colonialism. In spite of the divisions of partition, diaspora communities can be found living alongside one another in different parts of the world.